This is a translation of the third chapter of Jeyamohan’s அருகர்களின் பாதை.

Known as the Jain Kashi, the name Moodbidri is derived from two words: Moodu and Bidri. It means “Eastern Bamboo Country.” In inscriptions, it is referred to as Mooduvenupura. There are nearly 300 Jain temples in Moodbidri. For two hundred years, starting from the 14th century, Moodbidri continued to grow. Of the temples here, 18 are considered important, and among those, the Guru Basadi, Tribhuvana Tilaka Chudamani Basadi, and Ammanavara Basadi are the most ancient. The Thousand Pillar Basadi was right in front of our lodge, but we were told it would only open at seven o’clock. In the street lined with the eighteen Basadis, many appeared to be in a near-abandoned state. As we walked around, dried grass and touch-me-nots pricked our feet. Surprisingly, the Guru Basadi was open.

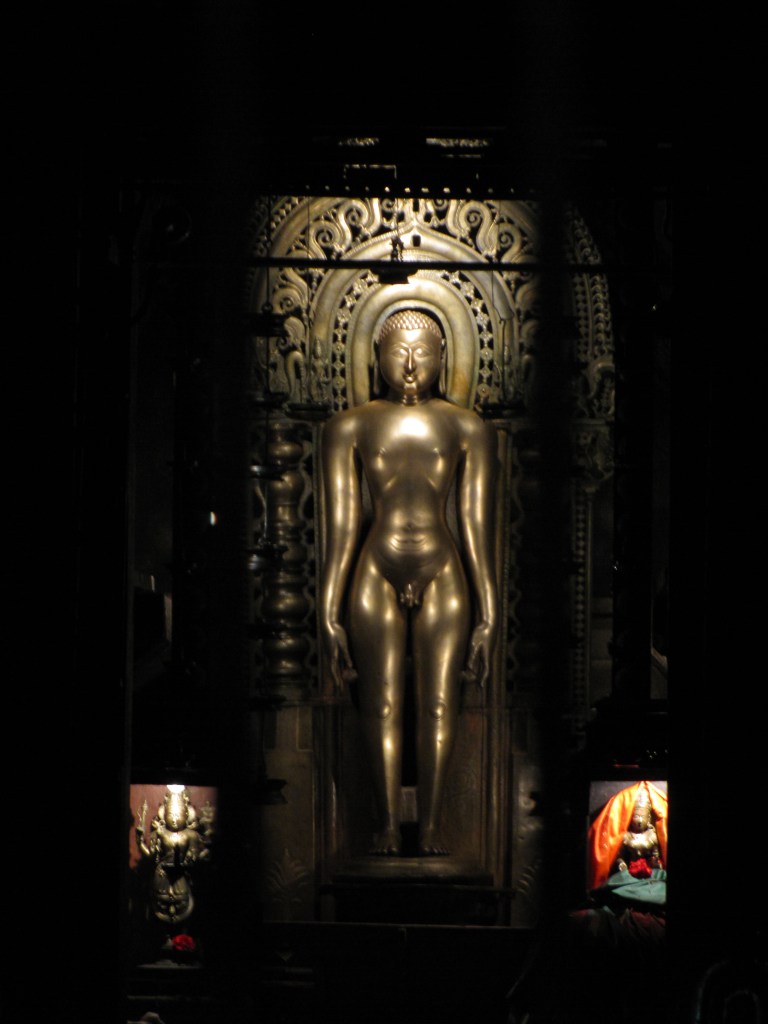

Built in the 7th century AD, the Guru Basadi is also known as the Siddhanatha Basadi or Hale Basadi (Old Basadi). This temple is dedicated to the twenty-third Tirthankara, Parshvanatha. He stands in the sanctum as a beautiful statue, three and a half meters tall. Rare palm-leaf manuscripts of Jain texts from the 12th century were discovered in this temple; these are known as the Dhavala works. In a separate shrine to the side of the temple, the twenty-four Tirthankaras stood with a pitch-black shine. They looked like twenty-four black diamonds. A Jain priest was performing puja for the central figure, Parshvanatha, chanting mantras in Sanskrit with precise pronunciation. In Hindu temples, mantras are mostly chanted in the Anushtup meter, and the pronunciation often feels blurred. I have heard pujas with good Sanskrit pronunciation rarely in Kerala temples, but I had never encountered a moment where Sanskrit was pronounced so beautifully until now. Hearing the Jain mantras here in a different meter (Shardula Vikriditam) and a distinct pronunciation created an emotional uplift that morning.

We walked around the Guru Basadi. The temple was shrouded in darkness. It was a massive structure made of stone, with internal partition brick walls containing windows. Instead of statues of Dvarapalas (gatekeepers), there were two paintings. It was surprising to see the Dvarapalas holding the conch, discus, and mace. It was also surprising to see statues of Krishna on the pillars in these temples. I had noticed and written about this during my very first visit here years ago. In reality, aside from very rare religious conflicts, Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism in India have generally coexisted and mingled naturally. There is a particularly close relationship between Jainism and Vaishnavism. “Progressive” historians who write history by blowing religious conflicts out of proportion have never cared for the compromise and togetherness that existed then and continues to exist here today. These sites completely demolish the prejudiced portrayal they create regarding India and Hinduism.

We walked past Guru Basadi through the courtyards of the closed temples. Giant peepal trees were waking up, scooping up the morning. The peace dripping from the leaves rustling in the breeze seemed to fill our minds. This town has remained unchanged for twenty years – the same old buildings, the same streets filled with contentment, peace, and antiquity. The red dust creates an illusion that we are in a century past.

After having another cup of tea, we went to the temple known as the Big Basadi or the Thousand Pillar Basadi. At first glance, it gives the impression of a massive Chinese Buddhist shrine. It features a three-tiered, pagoda-style wooden roof, beneath which lies a temple made of granite. This style of temple cannot be found outside of Canara. There is no tower above the large stone pillars, only a stone roof that slopes just like a wooden one. It looked as if a gigantic wooden temple had been transformed into stone by magic. A priest welcomed us warmly and spoke about the temple. He said, “You and we belong to the same religion, almost the same God, with only small differences.” He kept repeating this. He was surprised that we had come from such a long distance.

The Tribhuvana Chudamani Basadi is the largest of the temples here. It also possesses the most beautiful sculptural workmanship among the Jain temples of Karnataka. Known also as the Thousand Pillar Temple, this massive stone structure was built around 1430. A two-and-a-half-meter tall statue of Chandranatha Tirthankara stands at its center. This three-story stone edifice is cited as a prime example of Jain architecture. The open front hall (Mukhamandapa) of this temple is incredibly beautiful. Its pillars display the peak possibilities of granite carving; a single pillar alone could be considered a great work of art. I told my friends that if a single pillar from this temple existed in some European countries, they would declare it a national monument and showcase it as a major event. Queen Nagaladevi, the wife of King Bhairavaraja, created the massive fifty feet tall monolithic flagstaff that stands in front of this temple. An inscription about her is found on it. The pillars (Stambhas) in front of Jain temples are great marvels; atop these monolithic pillars, there is usually a Yaksha or Yakshi, with a guardian deity sitting at the base. Among the Yakshis, Kushmandini and Padmavati appear repeatedly.

There are hundreds of small Jain temples all over Moodbidri. One would need to wander continuously for a week to see all of Moodbidri. Some of the Jain temples here contain Tamil inscriptions. Most of the temples were built by merchants known here as Shettis, including Chettiars from the Chola country. There is even a Basadi built by the Chola princess Kundavai. All of this is yet to be researched by Tamil historians.

We left for Venur around 8:00 AM. Traveling through the morning sun along a road surrounded by lush green groves, we reached Venur. Venur is situated on the banks of the Phalguni River. It was once the spiritual capital of the Jains. Dharmasthala was once under the control of Venur. Inside the Jain temple in the center of this town stands a 38-foot tall statue of Bahubali. It was erected in 1604 by the Jain King Thimmanna of the Ajila dynasty and was carved by Jakanachari, who was known as the ‘Amarasilpi’ (Immortal Sculptor). Venur’s old name was Gurupura, meaning the town where the Jain Mutt was located, though there is no Mutt there now.

The Ajila dynasty ruled with Venur as their capital from 1154 to 1786. The Ajila kings built several Jain temples and a Shiva temple in Venur. This magnificent statue can be called the crowning achievement of the Ajila kings. A Mahamastakabhisheka (Grand Consecration) was performed for the Venur Bahubali deity in 2012. Vasanthakumar and I witnessed the Mahamastakabhisheka performed for the Shravanabelagola Gomateshwara in 2006. That was a wonderful experience. Seeing the statue change colors right before one’s eyes like a great dream must be described as an artistic event. At that time, I thought to myself that if one comes to Mangalore by train, one can reach Venur in an hour, and one should try to visit. Venur lay in quiet solitude like a small village whenever we visited in the past. Now, renovation works are happening at the temple. Behind the Gomateshwara statue, work was underway to erect a massive scaffolding.

From Venur, we traveled to Karkala. Although the afternoon sun was out, the breeze remained cool. The temples of Karkala start before the boundary of the town itself. Unaware of this, we saw a temple standing in the middle of a large lake by the roadside and got down to see it. It was a massive lake filled with blooming lilies. There was a path leading to the center. It was a large tiled-roof Basadi. It was closed and in a state of some neglect. Sitting in the temple looking at the lake, I doubted whether the experience was actually happening or I was daydreaming. White storks and grey herons flew all over the lake. My friends hollered when they saw a large kite snatch a snake from the water, though I missed seeing it. Jains do not allow fishing, so the lakes are full of birds. This lake created by Ajila kings is called Ramasamudram.

Karkala is located 20 km from Moodbidri. It is a holy place for both Jains and Hindus. Inscriptions and literary evidence regarding this town are available from the 10th century onwards. In Jain history, it is mentioned as early as the 2nd century AD. Karkala means “Black Stone.” The word Karikallu has morphed into this name. This is one of the many proofs that Tamil might have been in use here around the 2nd century AD. The important sites in Karkala are two hills located near each other. On one stands the statue of Bahubali Swami. It is a 42-foot tall Gomateshwara statue. This too is a monolithic statue. It is the largest statue in Karnataka after Shravanabelagola. The statue at Shravanabelagola is a magnificent work of art; no other statue has been able to achieve its beauty and perfection. However, this is the most beautiful statue after that one.

The temple was locked when we arrived. We climbed the stone steps and sat looking at the statue through the gate. The priest, seeing us climb, came up and opened it, allowing us inside. We walked around the statue and paid our respects. This grandeur had become accustomed to our eyes and minds. By now, Bahubali Swami had become a subconscious image. Cuddalore Seenu said that Bahubali statues appear in his dreams.

Karkala is home to eighteen Jain temples. Among the Hindu temples, the Anantha Padmanabha temple is important, though we did not attempt to see all the Hindu temples. Among the Jain temples, we visited only the Chaturmukha Basadi. It is located on another hill, a monolithic rock hill with rock-cut steps. A massive Basadi stands on top. It has an identical pillared entrance on all four sides with heavy, tall pillars. There are four sanctums opening in four directions, each containing three statues, making a total of twelve standing Tirthankara statues. Light reflected off the pitch-black marble statues. A lone lady who was there told us about the temple in whatever Hindi and Kannada she could manage.

Krishnan suggested that we stay in Karkala itself. But our journey was long; I felt as if the vastness of India was looming over us, and so I said we should move on. We set out for Varanga, a tiny hamlet beyond Karkala. To get there, one must take a side path on the way to Agumbe. There is a Jain mutt here – a local branch of the Humcha Jain Monastery. This monastery is an ancient building, reminiscent of Kerala architecture. A 12th-century inscription found here describes this mutt as being exceptionally ancient.

This mutt belongs to the Mesha Padhasha Gachha lineage, descending from the Mula Kundukundanvaya Kranurgana line of Acharya Kundakunda. It is said that this monastery may have existed here since the 4th century CE. We went to the mutt to ask for a place to stay. However, we were told that because an elderly Jain nun was residing there, non-Jains were not permitted to stay. We would have to wait until tomorrow to fully explore Varanga.

Near the mutt, situated in the middle of a vast lake, is a Basadi. In truth, it is a Stambha (pillar) with Tirthankara idols on all four sides, around which they have constructed a Basadi. It can only be reached by boat. We stood on the shore and watched the reflection of the Basadi in the water. Behind it lay low hills covered in lush green forest. Though the water was filled with algae, it remained crystal clear. You could sense the chill of the water just from the breeze. The lake was teeming with fish, leaping over the surface as if the water were boiling.

The priest, who also doubled as the boatman, took us to the temple. The aesthetic fulfillment offered by a temple surrounded by a lotus pond is beyond words. On the far shore, a multitude of birds gathered like a great assembly in the mud. We circumambulated the temple and offered our worship. The priest performed puja, chanting the mantras elaborately.

We asked the priest if we could stay nearby. He offered to speak to the authorities at the nearby Rama temple and arranged for us to stay for free at the temple’s marriage hall. On the way back, Aranga, Krishnan, Vinoth, Muthukrishnan, and I jumped into the water and swam alongside the boat. It was probably fifteen years since I had swam like that. I was a little out of breath, but when I climbed onto the shore, I felt reborn.

We stayed the night at the marriage hall. There was a small road junction nearby with two restaurants; only one had dosas available, and the owner warned us he would close by seven. We all had dinner there. Varanga is a tiny village – just a few houses clustered around the monastery and the three Jain temples. That night, we sat by the lakeside and talked. The sky was sharp and clear, filled with stars. During the brief power outage, the stars shone even more brilliantly. The stars, the mountains, the lake, and the temple all stretched out before our eyes, defined only by the varying depths of the darkness. It was a moment of realizing how magnificent darkness can be. We sat there in silence for a while.

We slept in the massive, spacious marriage hall. We spread out the tarpaulin used to cover our suitcases on top of our vehicle to lay down. It wasn’t very cold yet, though I suspected the chill would set in toward dawn. I remarked that we had never managed to find such a large “room” until now.